A Brief History of the Internet (Part 1)

The Code and the Crash

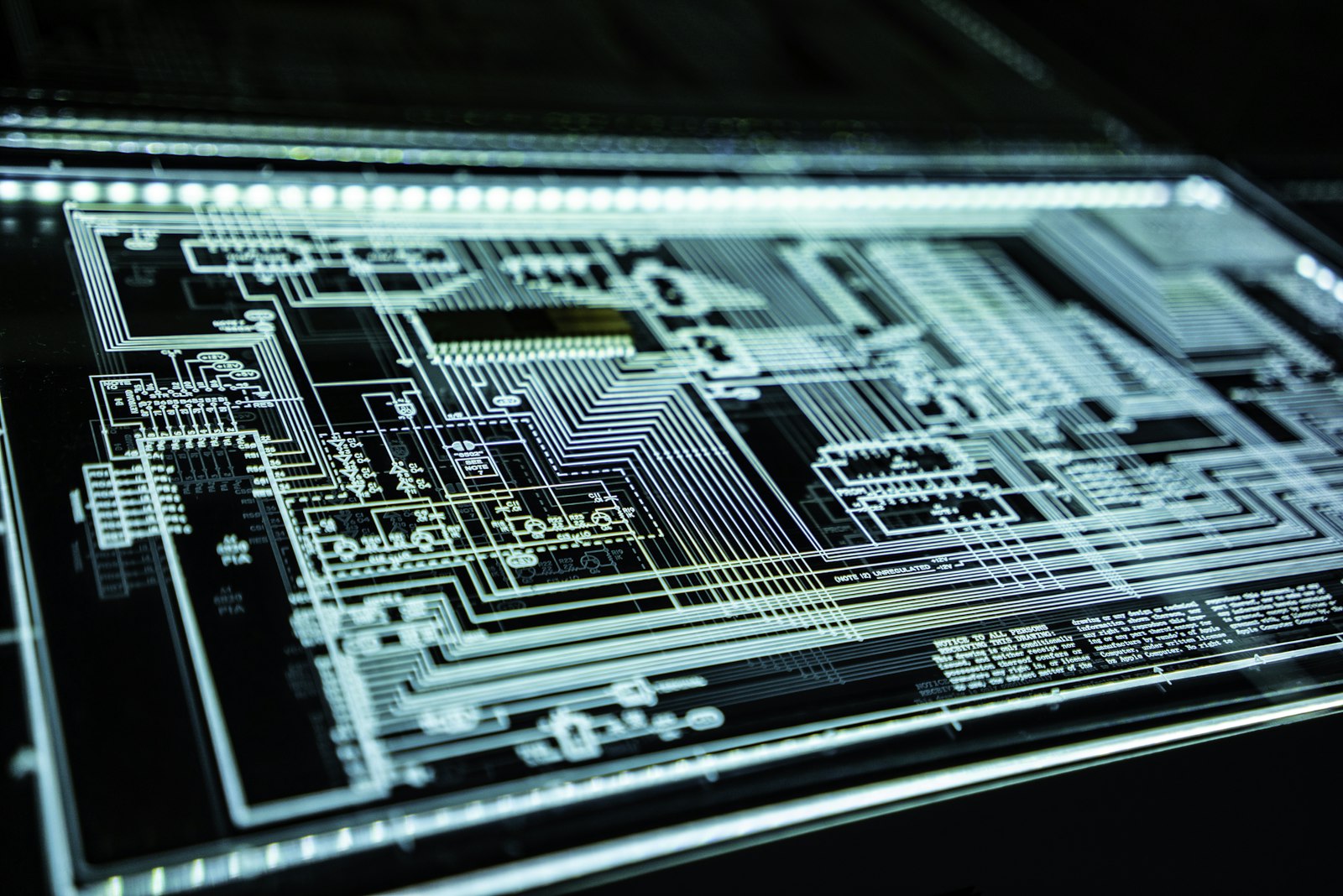

To understand the digital landscape of today, we must revisit the architecture of yesterday. My journey began not in a boardroom, but with an Amstrad CPC 1628 in the 1980s. In that era, "home computing" was a frontier concept. The lack of available software forced a generation of us to become creators by necessity, teaching ourselves to code simply to make the machine useful.

By the 1990s, as a professional programmer in London, I witnessed the first tectonic shift. IBM mainframes were giving way to personal computing, yet businesses were paralyzed by the human-tech disconnect. I realized then that the opportunity lay not in the hardware, but in the translation layer—bridging the gap between binary code and business strategy.

The Silicon Valley Illusion

When Vision Outpaces Reality

In 1999, I arrived in Silicon Valley at the peak of the Dot-Com frenzy. It was a time of irrational exuberance. Venture capitalists were pouring billions into e-commerce startups on a single, flawed premise: "If we build it, they will come."

We built virtual storefronts for a public that was not yet ready to shop digitally. We became paper millionaires overnight, blinded by the technology and oblivious to the sociology. When the crash came in 2000, it was a brutal correction of market reality.

"Vision devoid of pragmatic empathy builds only an illusion. Like Icarus, sky-high hopes melt swiftly when the human dimension lags behind technology's inexorable march."

The lesson remains vital for every digital strategist today: Innovation requires public readiness. You cannot force a revolution; you must time it.

BUY THE BOOK